-40%

Ancient Byzantine Empire Coin MAURICE TIBERIUS Bronze Decanummium Constantinople

$ 23.65

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

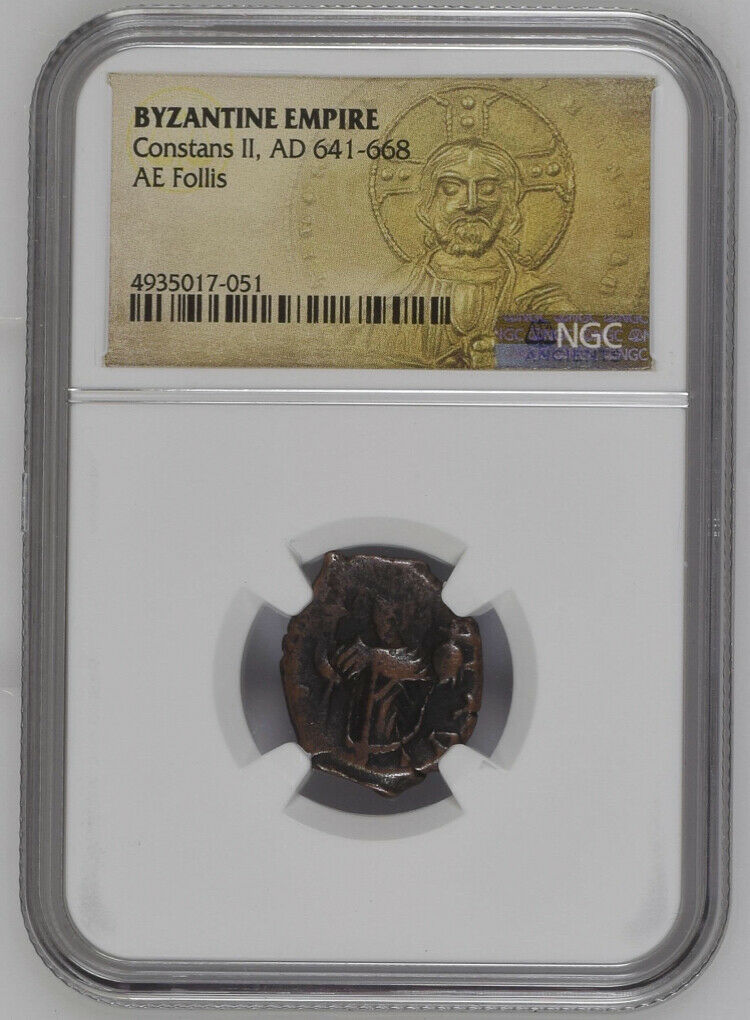

BYZANTINE EMPIRE

Ancient Coin

AE Bronze Decanummium

MAURICE TIBERIUS

Flavius Mauricius Tiberius

Byzantine Emperor 582-602AD

Obv: DN MAVRIC PP AVG

Crowned Maurice Tiberius facing, holding cross and globe

Rev: Large I, star left

Cross above, officina B right

CON in ex

Constantinople Mint

16.00 mm

PRIVATE

ANCIENT COINS COLLECTION

SOUTH FLORIDA ESTATE SALE

( Please, check out other ancient coins we have available for sale. We are offering 1000+ ancient coins collection)

ALL COINS ARE GENUINE

LIFETIME GUARANTEE

AND PROFESSIONALLY ATTRIBUTED

The attribution label is printed on archival museum quality paper

An interesting Byzantine coin of Maurice Tiberius. Bust of

Maurice Tiberius

on obverse and large I on reverse. This coin comes with display case, stand and attribution label attached as pictured.

A great way to display an ancient coins collection. You are welcome to ask any questions prior buying or bidding. We can ship it anywhere within continental U.S. for a flat rate of 6.90$. It includes shipping, delivery confirmation and packaging material.

Limited Time Offer:

FREE SHIPPING

(only within the continental U.S.)

The residents of HI/AK/U.S. Territories and International bidders/buyers must contact us for the shipping quote before bidding/buying

MAURICE TIBERIUS

Maurice Tiberius (Latin: Flavius Mauricius Tiberius Augustus (539 – 27 November 602) was Byzantine Emperor from 582 to 602.

A prominent general in his youth, Maurice fought with success against the Sassanid Persians. Once he became Emperor, he brought the war with Persia to a victorious conclusion: the Empire's eastern border in the Caucasus was vastly expanded and for the first time in nearly two centuries the Romans were no longer obliged to pay the Persians thousands of pounds of gold annually for peace.

Maurice campaigned extensively in the Balkans against the Avars – pushing them back across the Danube by 599. He also conducted campaigns across the Danube, the first Emperor to do so in over two hundred years. In the West, he established two large semi-autonomous provinces called exarchates, ruled by exarchs, or viceroys, of the emperor.

In Italy, Maurice established the Exarchate of Ravenna in 584, the first real effort by the Empire to halt the advance of the Lombards. With the creation of the Exarchate of Africa in 590, he further solidified the empire's hold on the western Mediterranean.

His reign was troubled by financial difficulties and almost constant warfare. In 602, a dissatisfied general named Phocas usurped the throne, having Maurice and his six sons executed. This event would prove cataclysmic for the Empire, sparking a devastating war with Persia that would leave both empires weakened prior to the Muslim invasions.

His reign is a relatively accurately documented era of Late Antiquity, in particular by the historian Theophylact Simocatta. Maurice also authored the Strategikon, a manual of war which influenced European militaries for nearly a millennium. He stands out as one of the last Emperors whose Empire still bore a strong resemblance to the Roman Empire of previous centuries. His reign is often considered the end of Classical antiquity.

Maurice was born in Arabissus in Cappadocia in 539, the son of a certain Paul. He had one brother, Peter, and two sisters, Theoctista and Gordia, later the wife of the general Philippicus. According to a legend, he was of Armenian origin, but the issue cannot be determined in any way. The historian Evagrius Scholasticus records a (likely invented) descent from old Rome.

Maurice first came to Constantinople as a notarius, and came to serve as a secretary to the comes excubitorum (commander of the Excubitors, the imperial bodyguard) Tiberius, the future Tiberius II (r. 578–582). When Tiberius was named Caesar in 574, Maurice was appointed to succeed him as comes excubitorum.

In late 577, despite a complete lack of military experience, Maurice was named as magister militum per Orientem, effectively commander-in-chief of the Byzantine army in the East, in the ongoing war against Sassanid Persia, succeeding the general Justinian. At about the same time, he was raised to the rank of patricius. He scored a decisive victory against the Persians in 581. A year later, he married Constantina, the Emperor's daughter. On 13 August, he succeeded his father-in-law as Emperor. Upon his ascension he ruled a bankrupt Empire. At war with Persia, paying extremely high tribute to the Avars, and the Balkan provinces thoroughly devastated by the Slavs, the situation was tumultuous at best.

Maurice had to continue the war against the Persians. In 586, his troops defeated them at a major battle south of Dara. Despite a serious mutiny in 588, the army managed to continue the war and even secure a major victory before Martyropolis. In 590, Prince Khosrau II and Persian commander-in-chief Bahram Chobin overthrew king Hormizd IV. Bahram Chobin claimed the throne for himself and defeated Khosrau, who subsequently fled to the Byzantine court. Although the Senate advised against it with one voice, Maurice assisted Khosrau to regain his throne with an army of 35,000 men. In 591 the combined Byzantine-Persian army under generals John Mystacon and Narses defeated Bahram Chobin's forces near Ganzak at the Battle of Blarathon. The victory was decisive; Maurice finally brought the war to a successful conclusion by means of a new accession of Khosrau.

Subsequently, Khosrau was probably adopted by the emperor. Khosrau further rewarded Maurice by ceding to the Empire western Armenia up to the lakes Van and Sevan, including the large cities of Martyropolis, Tigranokert, Manzikert, Ani, and Yerevan. Maurice's treaty brought a new status-quo to the east territorially, enlarged to an extent never before achieved by the Empire, and much cheaper to defend during this new perpetual peace – millions of solidi were saved by the remission of tribute to the Persians alone. Afterwards, Maurice imposed a union between the Armenian Church and the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

In 602, Maurice, always dealing with the lack of money, decreed that the army should stay for winter beyond the Danube, which would prove to be a serious mistake. The exhausted troops mutinied against the Emperor. Probably misjudging the situation, Maurice repeatedly ordered his troops to start a new offensive rather than returning to winter quarters. After a while, his troops gained the impression that Maurice no longer mastered the situation, proclaimed Phocas their leader, and demanded that Maurice abdicate and proclaim as successor either his son Theodosius or General Germanus. Both men were accused of treason, but riots broke out in Constantinople, and the emperor left the city with his family for Nicomedia. Theodosius headed east to Persia, but historians are not sure whether he had been sent there by his father or if he had fled there. Phocas entered Constantinople in November and was crowned Emperor, while his troops captured Maurice and his family.

Maurice was murdered on 27 November 602 (some say 23 November). It is said that the deposed emperor was forced to watch his six sons executed before he was beheaded himself. Empress Constantina and her three daughters were spared and sent to a monastery. The Persian King Khosrau II used this coup and the murder of his patron as an excuse for a renewed war against the Empire.

Maurice is seen as an able emperor and commander-in-chief, though the description by Theophylact may be a bit too glorifying. He possessed insight, public spirit, and courage. He proved his expertise on military and foreign affairs during his campaigns against Persians, Avars and Slavs as during peace negotiations with Khosrau II. His administrative reforms portray him as a statesman with farsightedness, all the more since they outlasted his death by far and were the basis for the introduction of the themes as military districts.

His court still used Latin, like the army and administration, and he promoted science and the arts. Maurice is traditionally named as author of the military treatise, Strategikon, which is praised in military circles as the only sophisticated combined arms theory until World War II. Some historians, however, now believe the Strategikon is the work of his brother or another general in his court.

His greatest weakness was his inability to judge how unpopular his decisions were. As summarized by the historian Previté-Orton, listing a number of character flaws in the Emperor's personality:

“ His fault was too much faith in his own excellent judgment without regard to the disagreement and unpopularity which he provoked by decisions in themselves right and wise. He was a better judge of policy than of men. ”

It was this flaw that cost him throne and life and thwarted most of his efforts to prevent the disintegration of the great empire of Justinian I. Maurice attempted to exercise the old Imperium Romanum, but, as his end shows, he met strong resistance.

The demise of Maurice was a turning point in history. The resulting war against Persia weakened both empires, enabling the Slavs to permanently settle the Balkans and paving the way for Arab/Muslim expansion. English historian A.H.M. Jones characterizes the death of Maurice as the end of the era of Classical Antiquity, as the turmoil that shattered the Empire in the next four decades permanently and thoroughly changed society and politics.

BYZANTINE EMPIRE

The Byzantine Empire was a vast and powerful civilization with origins that can be traced to 330 A.D., when the Roman emperor Constantine I dedicated a “New Rome” on the site of the ancient Greek colony of Byzantium. Though the western half of the Roman Empire crumbled and fell in 476 A.D., the eastern half survived for 1,000 more years, spawning a rich tradition of art, literature and learning and serving as a military buffer between Europe and Asia. The Byzantine Empire finally fell in 1453, after an Ottoman army stormed Constantinople during the reign of Constantine XI.

Byzantium

The term “Byzantine” derives from Byzantium, an ancient Greek colony founded by a man named Byzas. Located on the European side of the Bosporus (the strait linking the Black Sea to the Mediterranean), the site of Byzantium was ideally located to serve as a transit and trade point between Europe and Asia.

In 330 A.D., Roman Emperor Constantine I chose Byzantium as the site of a “New Rome” with an eponymous capital city, Constantinople. Five years earlier, at the Council of Nicaea, Constantine had established Christianity — once an obscure Jewish sect — as Rome’s official religion.

The citizens of Constantinople and the rest of the Eastern Roman Empire identified strongly as Romans and Christians, though many of them spoke Greek and not Latin.

Byzantine Empire Flourishes

The eastern half of the Roman Empire proved less vulnerable to external attack, thanks in part to its geographic location.

With Constantinople located on a strait, it was extremely difficult to breach the capital’s defenses; in addition, the eastern empire had a much smaller common frontier with Europe.

It also benefited greatly from a stronger administrative center and internal political stability, as well as great wealth compared with other states of the early medieval period. The eastern emperors were able to exert more control over the empire’s economic resources and more effectively muster sufficient manpower to combat invasion.

Eastern Roman Empire

As a result of these advantages, the Eastern Roman Empire, variously known as the Byzantine Empire or Byzantium, was able to survive for centuries after the fall of Rome.

Though Byzantium was ruled by Roman law and Roman political institutions, and its official language was Latin, Greek was also widely spoken, and students received education in Greek history, literature and culture.

In terms of religion, the Council of Chalcedon in 451 officially established the division of the Christian world into separate patriarchates, including Rome (where the patriarch would later call himself pope), Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem.

Even after the Islamic empire absorbed Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem in the seventh century, the Byzantine emperor would remain the spiritual leader of most eastern Christians.

Iconoclasm

During the eighth and early ninth centuries, Byzantine emperors (beginning with Leo III in 730) spearheaded a movement that denied the holiness of icons, or religious images, and prohibited their worship or veneration.

Known as Iconoclasm—literally “the smashing of images”—the movement waxed and waned under various rulers, but did not end definitively until 843, when a Church council under Emperor Michael III ruled in favor of the display of religious images.

Byzantine Art

During the late 10th and early 11th centuries, under the rule of the Macedonian dynasty founded by Michael III’s successor, Basil, the Byzantine Empire enjoyed a golden age.

Though it stretched over less territory, Byzantium had more control over trade, more wealth and more international prestige than under Justinian. The strong imperial government patronized Byzantine art, including now-cherished Byzantine mosaics.

Rulers also began restoring churches, palaces and other cultural institutions and promoting the study of ancient Greek history and literature.

Greek became the official language of the state, and a flourishing culture of monasticism was centered on Mount Athos in northeastern Greece. Monks administered many institutions (orphanages, schools, hospitals) in everyday life, and Byzantine missionaries won many converts to Christianity among the Slavic peoples of the central and eastern Balkans (including Bulgaria and Serbia) and Russia.

The Crusades

The end of the 11th century saw the beginning of the Crusades, the series of holy wars waged by European Christians against Muslims in the Near East from 1095 to 1291.

With the Seijuk Turks of central Asia bearing down on Constantinople, Emperor Alexius I turned to the West for help, resulting in the declaration of “holy war” by Pope Urban II at Clermont, France, that began the First Crusade.

As armies from France, Germany and Italy poured into Byzantium, Alexius tried to force their leaders to swear an oath of loyalty to him in order to guarantee that land regained from the Turks would be restored to his empire. After Western and Byzantine forces recaptured Nicaea in Asia Minor from the Turks, Alexius and his army retreated, drawing accusations of betrayal from the Crusaders.

During the subsequent Crusades, animosity continued to build between Byzantium and the West, culminating in the conquest and looting of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

The Latin regime established in Constantinople existed on shaky ground due to the open hostility of the city’s population and its lack of money. Many refugees from Constantinople fled to Nicaea, site of a Byzantine government-in-exile that would retake the capital and overthrow Latin rule in 1261.

Fall of Constantinople

During the rule of the Palaiologan emperors, beginning with Michael VIII in 1261, the economy of the once-mighty Byzantine state was crippled, and never regained its former stature.

In 1369, Emperor John V unsuccessfully sought financial help from the West to confront the growing Turkish threat, but he was arrested as an insolvent debtor in Venice. Four years later, he was forced–like the Serbian princes and the ruler of Bulgaria–to become a vassal of the mighty Turks.

As a vassal state, Byzantium paid tribute to the sultan and provided him with military support. Under John’s successors, the empire gained sporadic relief from Ottoman oppression, but the rise of Murad II as sultan in 1421 marked the end of the final respite.

Murad revoked all privileges given to the Byzantines and laid siege to Constantinople; his successor, Mehmed II, completed this process when he launched the final attack on the city. On May 29, 1453, after an Ottoman army stormed Constantinople, Mehmed triumphantly entered the Hagia Sophia, which would soon be converted to the city’s leading mosque.

The fall of Constantinople marked the end of a glorious era for the Byzantine Empire. Emperor Constantine XI died in battle that day, and the Byzantine Empire collapsed, ushering in the long reign of the Ottoman Empire.

Legacy of the Byzantine Empire

In the centuries leading up to the final Ottoman conquest in 1453, the culture of the Byzantine Empire–including literature, art, architecture, law and theology–flourished even as the empire itself faltered.

Byzantine culture would exert a great influence on the Western intellectual tradition, as scholars of the Italian Renaissance sought help from Byzantine scholars in translating Greek pagan and Christian writings. (This process would continue after 1453, when many of these scholars fled from Constantinople to Italy.)

Long after its end, Byzantine culture and civilization continued to exercise an influence on countries that practiced its Eastern Orthodox religion, including Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece, among others.

SHIPPING INFO:

- The Shipping Charge is a flat rate and it includes postage, delivery confirmation, insurance up to the value (if specified), shipping box (from 0.99$ to 5.99$ depends on a size) and packaging material (bubble wrap, wrapping paper, foam if needed)

- We can ship this item to all continental states. Please, contact us for shipping charges to Hawaii and Alaska.

- We can make special delivery arrangements to Canada, Australia and Western Europe.

- USPS (United States Postal Service) is the courier used for ALL shipping.

- Delivery confirmation is included in all U.S. shipping charges. (No Exceptions)

CONTACT/PAYMENT INFO:

- We will reply to questions & comments as quickly as we possibly can, usually within a day.

- Please ask any questions prior to placing bids.

- Acceptable form of payment is PayPal

REFUND INFO:

- All items we list are guaranteed authentic or your money back.

- Please note that slight variations in color are to be expected due to camera, computer screen and color

pixels and is not a qualification for refund.

- Shipping fees are not refunded.

FEEDBACK INFO:

- Feedback is a critical issue to both buyers and sellers on eBay.

- If you have a problem with your item please refrain from leaving negative or neutral feedback until you have made contact and given a fair chance to rectify the situation.

- As always, every effort is made to ensure that your shopping experience meets or exceeds your expectations.

- Feedback is an important aspect of eBay. Your positive feedback is greatly appreciated!