-40%

Ancient Byzantine Empire Coin JUSTINIAN I Constantinople Mint Bronze

$ 21.06

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

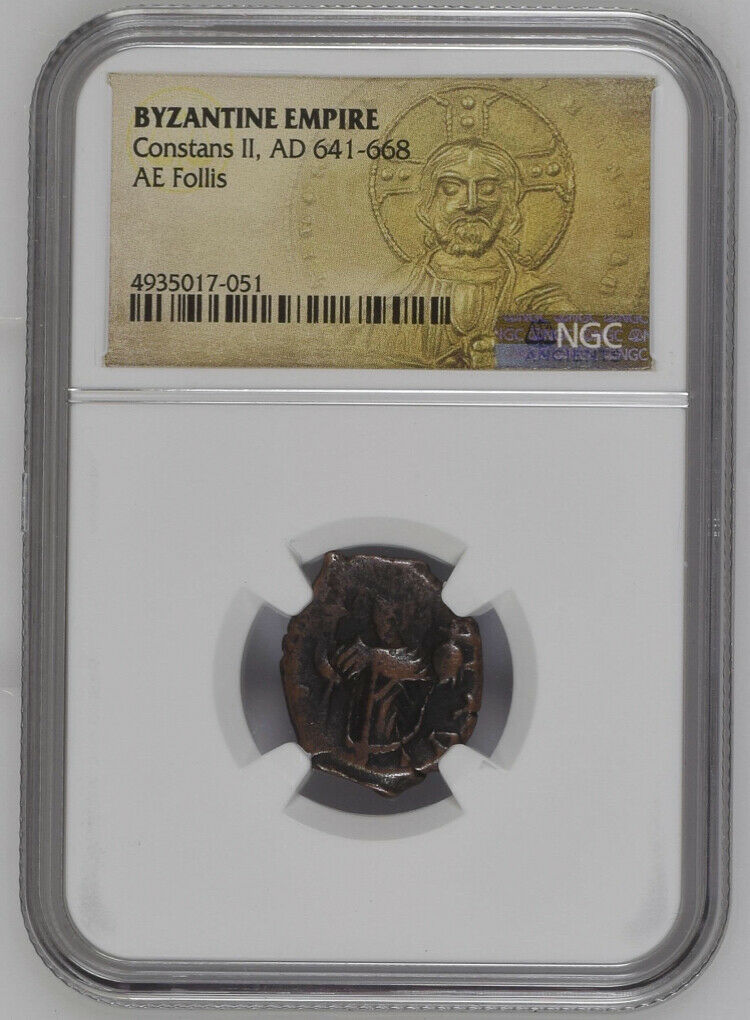

BYZANTINE EMPIRE

Ancient Coin

AE Bronze Half Follis

JUSTINIAN I

Petrus Sabbatus Iustinianus

Byzantine Emperor 527-565AD

Obv: DN IVSTINIANVS PP AV

Diademed bust of Justinian I facing

Rev: Large K, ANNO left

Cross above, Officina letter right

Constantinople Mint

22.00 mm

PRIVATE

ANCIENT COINS COLLECTION

SOUTH FLORIDA ESTATE SALE

( Please, check out other ancient coins we have available for sale. We are offering 1000+ ancient coins collection)

ALL COINS ARE GENUINE

LIFETIME GUARANTEE

AND PROFESSIONALLY ATTRIBUTED

The attribution label is printed on archival museum quality paper

An interesting Byzantine coin of Justinian I. Bust of Justinian I

on obverse and large K on reverse. This coin comes with display case, stand and attribution label attached as pictured.

A great way to display an ancient coins collection. You are welcome to ask any questions prior buying or bidding. We can ship it anywhere within continental U.S. for a flat rate of 6.90$. It includes shipping, delivery confirmation and packaging material.

Limited Time Offer:

FREE SHIPPING

(only within the continental U.S.)

The residents of HI/AK/U.S. Territories and International bidders/buyers must contact us for the shipping quote before bidding/buying

JUSTINIAN I

Justinian, or Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Justinianus, was arguably the most important ruler of the Eastern Roman Empire. Considered by some scholars to be the last great Roman emperor and the first great Byzantine emperor, Justinian fought to reclaim Roman territory and left a lasting impact on architecture and law. His relationship with his wife, Empress Theodora, would play an essential role in the course of his reign.

Justinian's Early Years

Justinian, whose given name was Petrus Sabbatius, was born in 483 CE to peasants in the Roman province of Illyria. He may have still been in his teens when he came to Constantinople. There, under the sponsorship of his mother's brother, Justin, Petrus acquired a superior education. However, thanks to his Latin background, he always spoke Greek with a notable accent.

At this time, Justin was a highly-ranked military commander, and Petrus was his favorite nephew. The younger man climbed the social ladder with a hand up from the older, and he held several important offices. In time, the childless Justin officially adopted Petrus, who took the name "Justinianus" in his honor. In 518, Justin became Emperor. Three years later, Justinian became a consul.

Justinian and Theodora

Sometime before the year 523, Justinian met the actress Theodora. If The Secret History by Procopius is to be believed, Theodora was a courtesan as well as an actress, and her public performances bordered on the pornographic. Later authors defended Theodora, claiming that she had undergone a religious awakening and that she found ordinary work as a wool spinner to support herself honestly.

No one knows precisely how Justinian met Theodora, but he appears to have fallen hard for her. She was not only beautiful, but she was also shrewd and able to appeal to Justinian on an intellectual level. She was also known for her passionate interest in religion; she had become a Monophysite, and Justinian may have taken a measure of tolerance from her plight. They also shared humble beginnings and were somewhat apart from Byzantine nobility. Justinian made Theodora a patrician, and in 525 — the same year that he received the title of Caesar — he made her his wife. Throughout his life, Justinian would rely on Theodora for support, inspiration, and guidance.

Rising to the Purple

Justinian owed much to his uncle, but Justin was well-repaid by his nephew. He had made his way to the throne through his skill, and he had governed through his strengths; but through much of his reign, Justin enjoyed the advice and allegiance of Justinian. This was especially true as the emperor's reign drew to a close.

In April of 527, Justinian was crowned co-emperor. At this time, Theodora was crowned Augusta. The two men would share the title for only four months before Justin passed away in August of that same year.

Emperor Justinian

Justinian was an idealist and a man of great ambition. He believed he could restore the empire to its former glory, both in terms of the territory it encompassed and the achievements made under its aegis. He wanted to reform the government, which had long suffered from corruption, and clear up the legal system, which was heavy with centuries of legislation and outmoded laws. He had great concern for religious righteousness and wanted persecutions against heretics and orthodox Christians alike to end. Justinian also appears to have had a sincere desire to improve the lot of all citizens of the empire.

When his reign as sole emperor began, Justinian had many different issues to deal with, all in the space of a few years.

Justinian's Early Reign

One of the very first things Justinian attended to was a reorganization of Roman, now Byzantine, Law. He appointed a commission to begin the first book of what was to be a remarkably extensive and thorough legal code. It would come to be known as the Codex Justinianus (the Code of Justinian). Although the Codex would contain new laws, it was primarily a compilation and clarification of centuries of existing law, and it would become one of the most influential sources in western legal history.

Justinian then set about instituting governmental reforms. The officials he appointed were at times too enthusiastic in rooting out long-entrenched corruption, and the well-connected targets of their reform did not go easily. Riots began to break out, culminating in the most famous Nika Revolt of 532. But thanks to the efforts of Justinian's able general Belisarius, the riot was ultimately put down; and thanks to the support of Empress Theodora, Justinian showed the kind of backbone that helped solidify his reputation as a courageous leader. Though he may not have been loved, he was respected.

After the revolt, Justinian took the opportunity to conduct a massive construction project that would add to his prestige and make Constantinople an impressive city for centuries to come. This included the rebuilding of the marvelous cathedral, the Hagia Sophia. The building program was not restricted to the capital city, but extended throughout the empire, and included the construction of aqueducts and bridges, orphanages and hostels, monasteries and churches; and it encompassed the restoration of entire towns destroyed by earthquakes (an unfortunately all-too-frequent occurrence).

In 542, the empire was struck by a devastating epidemic that would later be known as Justinian's Plague or the Sixth-Century Plague. According to Procopius, the emperor himself succumbed to the disease, but fortunately, he recovered.

Justinian's Foreign Policy

When his reign began, Justinian's troops were fighting Persian forces along the Euphrates. Although the considerable success of his generals (Belisarius in particular) would allow the Byzantines to conclude equitable and peaceful agreements, war with the Persians would flare up repeatedly through most of Justinian's reign.

In 533, the intermittent mistreatment of Catholics by the Arian Vandals in Africa came to a disturbing head when the Catholic king of the Vandals, Hilderic, was thrown into prison by his Arian cousin, who took his throne. This gave Justinian an excuse to attack the Vandal kingdom in North Africa, and once again his general Belisarius served him well. When the Byzantines were through with them, the Vandals no longer posed a serious threat, and North Africa became part of the Byzantine Empire.

It was Justinian's view that the western empire had been lost through "indolence," and he believed it his duty to re-acquire territory in Italy — especially Rome — as well as other lands that had once been part of the Roman Empire. The Italian campaign lasted well over a decade, and thanks to Belisarius and Narses, the peninsula ultimately came under Byzantine control — but at a terrible cost. Most of Italy was devastated by the wars, and a few short years after Justinian's death, invading Lombards were able to capture large portions of the Italian peninsula.

Justinian's forces were far less successful in the Balkans. There, bands of Barbarians continually raided Byzantine territory, and though occasionally repulsed by imperial troops, ultimately, Slavs and Bulgars invaded and settled within the borders of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Justinian and the Church

Emperors of Eastern Rome usually took a direct interest in ecclesiastical matters and often played a significant role in the direction of the Church. Justinian saw his responsibilities as emperor in this vein. He forbade pagans and heretics from teaching, and he closed the famous Academy for being pagan and not, as was often charged, as an act against classical learning and philosophy.

Though an adherent to Orthodoxy himself, Justinian recognized that much of Egypt and Syria followed the Monophysite form of Christianity, which had been branded a heresy. Theodora's support of the Monophysites undoubtedly influenced him, at least in part, to attempt to strike a compromise. His efforts did not go well. He tried to force western bishops to work with the Monophysites and even held Pope Vigilius in Constantinople for a time. The result was a break with the papacy that lasted until 610 CE.

Justinian's Later Years

After the death of Theodora in 548, Justinian showed a marked decline in activity and appeared to withdraw from public matters. He became deeply concerned with theological issues, and at one point even went so far as to take a heretical stand, issuing in 564 an edict declaring that the physical body of Christ was incorruptible and that it only appeared to suffer. This was immediately met with protests and refusals to follow the edict, but the issue was resolved when Justinian died suddenly on the night of November 14/15, 565.

His nephew, Justin II succeeded Justinian.

The Legacy of Justinian

For nearly 40 years, Justinian guided a burgeoning, dynamic civilization through some of its most turbulent times. Although much of the territory acquired during his reign was lost after his death, the infrastructure he succeeded in creating through his building program would remain. And while both his foreign expansion endeavors and his domestic construction project would leave the empire in financial difficulty, his successor would remedy that without too much trouble. Justinian's reorganization of the administrative system would last some time, and his contribution to legal history would be even more far-reaching.

After his death, and after the death of the writer Procopius (a highly respected source for Byzantine history), a scandalous exposé was published known to us as The Secret History. Detailing an imperial court rife with corruption and depravity, the work — which most scholars believe was indeed written by Procopius, as it was claimed — attacks both Justinian and Theodora as greedy, debauched and unscrupulous. While most scholars acknowledge the authorship of Procopius, the content of The Secret History remains controversial; and over the centuries, while it tarred the reputation of Theodora pretty badly, it has largely failed to reduce the stature of Emperor Justinian. He remains one of the most impressive and important emperors in Byzantine history.

BYZANTINE EMPIRE

The Byzantine Empire was a vast and powerful civilization with origins that can be traced to 330 A.D., when the Roman emperor Constantine I dedicated a “New Rome” on the site of the ancient Greek colony of Byzantium. Though the western half of the Roman Empire crumbled and fell in 476 A.D., the eastern half survived for 1,000 more years, spawning a rich tradition of art, literature and learning and serving as a military buffer between Europe and Asia. The Byzantine Empire finally fell in 1453, after an Ottoman army stormed Constantinople during the reign of Constantine XI.

Byzantium

The term “Byzantine” derives from Byzantium, an ancient Greek colony founded by a man named Byzas. Located on the European side of the Bosporus (the strait linking the Black Sea to the Mediterranean), the site of Byzantium was ideally located to serve as a transit and trade point between Europe and Asia.

In 330 A.D., Roman Emperor Constantine I chose Byzantium as the site of a “New Rome” with an eponymous capital city, Constantinople. Five years earlier, at the Council of Nicaea, Constantine had established Christianity — once an obscure Jewish sect — as Rome’s official religion.

The citizens of Constantinople and the rest of the Eastern Roman Empire identified strongly as Romans and Christians, though many of them spoke Greek and not Latin.

Byzantine Empire Flourishes

The eastern half of the Roman Empire proved less vulnerable to external attack, thanks in part to its geographic location.

With Constantinople located on a strait, it was extremely difficult to breach the capital’s defenses; in addition, the eastern empire had a much smaller common frontier with Europe.

It also benefited greatly from a stronger administrative center and internal political stability, as well as great wealth compared with other states of the early medieval period. The eastern emperors were able to exert more control over the empire’s economic resources and more effectively muster sufficient manpower to combat invasion.

Eastern Roman Empire

As a result of these advantages, the Eastern Roman Empire, variously known as the Byzantine Empire or Byzantium, was able to survive for centuries after the fall of Rome.

Though Byzantium was ruled by Roman law and Roman political institutions, and its official language was Latin, Greek was also widely spoken, and students received education in Greek history, literature and culture.

In terms of religion, the Council of Chalcedon in 451 officially established the division of the Christian world into separate patriarchates, including Rome (where the patriarch would later call himself pope), Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem.

Even after the Islamic empire absorbed Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem in the seventh century, the Byzantine emperor would remain the spiritual leader of most eastern Christians.

Iconoclasm

During the eighth and early ninth centuries, Byzantine emperors (beginning with Leo III in 730) spearheaded a movement that denied the holiness of icons, or religious images, and prohibited their worship or veneration.

Known as Iconoclasm—literally “the smashing of images”—the movement waxed and waned under various rulers, but did not end definitively until 843, when a Church council under Emperor Michael III ruled in favor of the display of religious images.

Byzantine Art

During the late 10th and early 11th centuries, under the rule of the Macedonian dynasty founded by Michael III’s successor, Basil, the Byzantine Empire enjoyed a golden age.

Though it stretched over less territory, Byzantium had more control over trade, more wealth and more international prestige than under Justinian. The strong imperial government patronized Byzantine art, including now-cherished Byzantine mosaics.

Rulers also began restoring churches, palaces and other cultural institutions and promoting the study of ancient Greek history and literature.

Greek became the official language of the state, and a flourishing culture of monasticism was centered on Mount Athos in northeastern Greece. Monks administered many institutions (orphanages, schools, hospitals) in everyday life, and Byzantine missionaries won many converts to Christianity among the Slavic peoples of the central and eastern Balkans (including Bulgaria and Serbia) and Russia.

The Crusades

The end of the 11th century saw the beginning of the Crusades, the series of holy wars waged by European Christians against Muslims in the Near East from 1095 to 1291.

With the Seijuk Turks of central Asia bearing down on Constantinople, Emperor Alexius I turned to the West for help, resulting in the declaration of “holy war” by Pope Urban II at Clermont, France, that began the First Crusade.

As armies from France, Germany and Italy poured into Byzantium, Alexius tried to force their leaders to swear an oath of loyalty to him in order to guarantee that land regained from the Turks would be restored to his empire. After Western and Byzantine forces recaptured Nicaea in Asia Minor from the Turks, Alexius and his army retreated, drawing accusations of betrayal from the Crusaders.

During the subsequent Crusades, animosity continued to build between Byzantium and the West, culminating in the conquest and looting of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

The Latin regime established in Constantinople existed on shaky ground due to the open hostility of the city’s population and its lack of money. Many refugees from Constantinople fled to Nicaea, site of a Byzantine government-in-exile that would retake the capital and overthrow Latin rule in 1261.

Fall of Constantinople

During the rule of the Palaiologan emperors, beginning with Michael VIII in 1261, the economy of the once-mighty Byzantine state was crippled, and never regained its former stature.

In 1369, Emperor John V unsuccessfully sought financial help from the West to confront the growing Turkish threat, but he was arrested as an insolvent debtor in Venice. Four years later, he was forced–like the Serbian princes and the ruler of Bulgaria–to become a vassal of the mighty Turks.

As a vassal state, Byzantium paid tribute to the sultan and provided him with military support. Under John’s successors, the empire gained sporadic relief from Ottoman oppression, but the rise of Murad II as sultan in 1421 marked the end of the final respite.

Murad revoked all privileges given to the Byzantines and laid siege to Constantinople; his successor, Mehmed II, completed this process when he launched the final attack on the city. On May 29, 1453, after an Ottoman army stormed Constantinople, Mehmed triumphantly entered the Hagia Sophia, which would soon be converted to the city’s leading mosque.

The fall of Constantinople marked the end of a glorious era for the Byzantine Empire. Emperor Constantine XI died in battle that day, and the Byzantine Empire collapsed, ushering in the long reign of the Ottoman Empire.

Legacy of the Byzantine Empire

In the centuries leading up to the final Ottoman conquest in 1453, the culture of the Byzantine Empire–including literature, art, architecture, law and theology–flourished even as the empire itself faltered.

Byzantine culture would exert a great influence on the Western intellectual tradition, as scholars of the Italian Renaissance sought help from Byzantine scholars in translating Greek pagan and Christian writings. (This process would continue after 1453, when many of these scholars fled from Constantinople to Italy.)

Long after its end, Byzantine culture and civilization continued to exercise an influence on countries that practiced its Eastern Orthodox religion, including Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece, among others.

SHIPPING INFO:

- The Shipping Charge is a flat rate and it includes postage, delivery confirmation, insurance up to the value (if specified), shipping box (from 0.99$ to 5.99$ depends on a size) and packaging material (bubble wrap, wrapping paper, foam if needed)

- We can ship this item to all continental states. Please, contact us for shipping charges to Hawaii and Alaska.

- We can make special delivery arrangements to Canada, Australia and Western Europe.

- USPS (United States Postal Service) is the courier used for ALL shipping.

- Delivery confirmation is included in all U.S. shipping charges. (No Exceptions)

CONTACT/PAYMENT INFO:

- We will reply to questions & comments as quickly as we possibly can, usually within a day.

- Please ask any questions prior to placing bids.

- Acceptable form of payment is PayPal

REFUND INFO:

- All items we list are guaranteed authentic or your money back.

- Please note that slight variations in color are to be expected due to camera, computer screen and color

pixels and is not a qualification for refund.

- Shipping fees are not refunded.

FEEDBACK INFO:

- Feedback is a critical issue to both buyers and sellers on eBay.

- If you have a problem with your item please refrain from leaving negative or neutral feedback until you have made contact and given a fair chance to rectify the situation.

- As always, every effort is made to ensure that your shopping experience meets or exceeds your expectations.

- Feedback is an important aspect of eBay. Your positive feedback is greatly appreciated!